…to find all the resources we will be using in class this semester.

Welcome to History of Mental Health in the US for Fall 2023

I’m looking forward to working with all of you this semester.

“That’s Too Much, Man”: Bojack Horseman and the Memory of Mental Health

I mean, I guess I got a happy ending, but every happy ending has the day after the happy ending, right? And the day after that.

Diane Nguyen, “One Trick Pony,” Bojack Horseman, Season 1, Episode 10

On its face, Bojack Horseman seems like any other adult animated Netflix series, the type the streaming giant churns out many of every year. Set in a fictionalized world of anthropomorphic animals who live alongside humans, the show follows the titular Bojack, the washed up star of a 1990s sitcom “Horsin’ Around”, and his struggles with his fame, addiction, and self-worth. Premiering on Netflix in 2014, the show initially garnered mediocre reviews, but over time it became well regarded for its narrative, tone, complexity, and humor, and by the end of the show’s run in 2020 upon the conclusion of its sixth season, was almost universally lauded for its quality, and its unflinchingly faithful depictions of mental health and its struggles.

Balancing a wry comedic tone with darker, more dramatic elements surrounding mental health issues, and themes of substance abuse, depression, trauma, etc, Bojack Horseman encapsulates much of the way that mental health is seen in popular perception today: as an issue that affects everyone, but easier to cope with through honesty, humor, and compassion. It is a deeply personal examination of the struggles that come from mental health challenges, and is a perfect realization of how mental health is seen and remembered in media in the US in the present day.

Bojack primarily follows the titular Horseman, and a supporting cast of four other characters close to Bojack as he navigates the tumultuous world of Hollywoo. Through these relationships, the show tackles many issues of mental health, such as substance abuse, depression, anxiety, trauma, among many others. Through that exploration, it also depicts the effects mental illness has on people, and how to live with, overcome, and grow in spite of such challenges. Bojack does this well through its run, and a few episodes of the series stand out as poignant examples of how mental health is popularly constructed, shown, and remembered.

I don’t believe in rock bottoms. I’ve had a lot of what I thought were rock bottoms only to discover – another rockier bottom underneath.

Bojack Horseman, “Xerox of a Xerox,” Bojack Horseman, Season 6, Episode 12

The show can be generally split in half, with the first three seasons being a gradual descent for Bojack, struggling deeply with his substance abuse, depression, narcissistic tendencies, indulging in his worst habits, and committing some of his most heinous acts. Season one’s “Downer Ending” introduces the audience to the severity of Bojack’s substance abuse problems, as well as the depth of his anxieties about his past and future. “Brand New Couch,” season two’s premiere, sees the perils of ignoring your mental health, and the hard work that it takes to actually address those issues. Season three is perhaps the lowest point for Bojack, with Todd chastising Bojack for his bad behavior and his attempts to abrogate his role in his behavior in “It’s You,” leading him to a drug-fueled bender with his Horsin’ Around co-star Sarah Lynn that results in her death, in “That’s Too Much, Man.”

The second half of the series shows Bojack’s attempts to better himself, and grow and change from his worst qualities, with many bumps along the road, and varied success. “The Old Sugarman Place” and Time’s Arrow” in season four revolve around Bojack’s mother, Beatrice, and how she passed on her childhood trauma to Bojack, being cold and abusive to him during his youth. Season five sees Bojack’s substance abuse at its worst, causing him to lose touch with reality, become paranoid, and hallucinate, culminating in his attack of a co-star in the penultimate episode of the season, “The Showstopper.” Bojack finally is put on the right path with season six’s “A Horse Walks Into Rehab,” finally growing beyond his worst behaviors by the series’ “happy ending” in “The Face of Depression.” But because there aren’t real happy endings in life, Bojack backslides into some of his worst patterns in the final episodes of the season, and ends the series on an upbeat, but bittersweet note in “Nice While It Lasted.”

Bojack Horseman believes that mental illness, living with it and growing in spite of it, is hard. There are no easy answers, no magic pills, no simple tricks that make it easier. Living with mental illness and experiencing the struggles that come with it means you have to try just as hard to be the best person you can be, and that no matter what happens on any one day, you keep on going. There are no happy endings, there’s only the day after. Its pragmatism, honesty, and relatability make it a prime example of how mental health is seen today, and how these candid depictions represent an evolution of popular memory of mental health.

Watch more: Bob-Waksberg, Raphael. BoJack Horseman. Tornante Television, 2014. https://www.netflix.com/title/70300800.

11/30

I chose this image because it shows the steps for someone to be involuntarily committed. It shows how much it has changed compared to Pete Earley’s Crazy.

Laughing Like Crazy

Psychiatry and the Evolution of Mental Health in American Comedy

I’ve been dealing with stuff more severe than that since a really young age. Um, I didn’t… I didn’t know when I was 11 years old that this thing had a name: Depression. I just thought everybody in fifth grade had an internal monologue like the guy from Taxi Driver.

Chris Gerhard, Career Suicide, 2017 1

INTRODUCTION

On December 27, 2016, actress Carrie Fisher passed away at the UCLA Medical Center in Los Angeles, CA, four days after falling unconscious on an LA-bound flight from London. Long candid about her challenges with mental health and substance abuse, toxicology reports after her death showed cocaine, heroin, MDMA, and other opiates in her system, in what likely contributed to her death.2 Her remains were split between a plot in Forest Lawn Memorial Park, and a giant novelty Prozac pill urn, a final gag, and recognition of the ways that that giant pill had likely saved her life before.3 Fisher’s body of work talking about her mental health, and in the end her Prozac proclivity, shines a spotlight well known to comedians and their audiences: the link between comedians and mental health challenges.

In traveling back through the annals of American comedy of various types, be it the classic stand-up comedy, film, television, etc, two major developments stood out in focusing on how comedy approached mental health. Specifically, the approach of comedy toward mental health fundamentally changed during the deinstitutionalization movement and the accompanying development and rise of psychiatric medication from the 1960s to the 70s, and made the discussion of mental health far more prescient and acceptable than it had ever been before.

I hope then, to take you on an exploration of how American comedy has addressed mental health over time, and how its depictions have evolved from its earliest roots, to the newest Netflix specials you see today. This story is told over more than a century, and includes vastly different kinds of expression, styles of humor, and types of media. All of these, however disparate that they may be, speak to a greater awareness, sensitivity, and focus in the comedic landscape towards issues of mental health, a shift that came from comics and audiences alike.

I was invited to go to a mental hospital. And… Well, you don’t want to be rude, right? So you go. Well, wait a… Wait a second now. It’s a really really

exclusive invitation. I mean, how many of you have been invited to a mental hospital?Carrie Fisher, Wishful Drinking5

DEINSTITUTIONALIZATION AND EMPTYING THE “LOONY BIN”

Humor and insanity frequently linked together in language and the popular imagination. One might laugh “like crazy” or “hysterically,” or someone with a peculiar personality might be described as “kooky,” “wacky,” or “bonkers,” words that have been used to refer to people who make you laugh, as well as people who are mentally ill. The “loony bin,” as one name the asylum came to be known by, is the start of this story, and the decline of this institution came to enable an era of openness around mental health and its struggles.

From its earliest days of development in the mid to late nineteenth century, the asylum was the birthplace of psychiatry, and arguably the idea of mental health. From its outset, the institutionalists sought to create a treatment environment that was meant to “cure” the mentally ill.6 This “moral treatment,” based on principles of humane and social care dominated the early days of the asylum, but fell to the wayside in the twentieth century as institutions became overcrowded, underfunded, and neglected. High profile exposés of asylums, like Nellie Bly’s famous Ten Days in a Madhouse, began to sour public opinions of the asylum, and along with astronomical costs of institutions, and the introduction of new psychiatric medications, American psychiatric institutions began to shudder their doors in the 50s, 60s, and 70s.7

This movement came to be known as deinstitutionalization, which saw institutions began to lower their admissions and discharge early, point their newly released patients towards secondary psychiatric care, and after they had shifted enough people away, they closed for good. Much of the practical outcome that deinstitutionalization sought was the shift towards community support, and while a noble goal, there were simply too many people released too quickly, which shortly outpaced the establishment of adequate support services.8

For many patients, deinstitutionalization meant liberation from the often dehumanizing and overcrowded conditions of asylums of the time, but for others, the loss of structure and more constant care was a significant problem. Some successfully adapted to community living, benefiting from outpatient care and medications, while yet others faced homelessness, prison or other legal issues, or burdened their loved ones, who ultimately assumed the responsibility of their care. As the loony bin began to empty out, the new frontier of psychiatric treatment began its meteoric rise.

Berle: [on the enthusiasm of Elvis’ female fans] You must be kidding, are you kidding? You don’t like it?

Presley: No, I-I’m not, I’ll tell ya, I’d rather have a quiet type of girl, someone more sedate, someone that’ll calm me down and relax me, y’know?

Berle: You don’t want a girl, you want a Miltown.

Elvis Presley and Milton Berle on The Milton Berle Show, April 3, 1956

“UNCLE MILTOWN” AND THE GROWTH OF PSYCHOTROPIC MEDICATIONS

Meprobamate, famously known as Miltown, was one of the first tranquilizers to hit the US market in 1955, and immediately showed positive results in institutionalized patients and the general public. Valium, another anti-anxiety medication, came around in 1959, and joined a cast of psychotropic characters like Chlorpromazine, an antipsychotic widely used in institutions in the 1950s.10 The effect that these medications had on psychiatric care was immediate and immense, and these medications allowed those in inpatient care to move out of the asylum, as many patients now did not need constant supervision and attention. Deinstitutionalization was largely enabled by these new “miracle drugs,” and came to be used widely outside the institutional setting.

The popularity of these psychiatric drugs grew immensely; as seen above, ads for drugs like Miltown touted that they “ relax both muscle and mind… without impairing physical or mental efficiency.” These drugs exploded in popularity among the general public, and were some of the most prescribed drugs in the 1950s and 60s. Tranquilizers took Hollywood by storm, and became popular with stars coping with their high stress lives. “Miltown” Berle, as he jokingly quipped, was a prominent proponent of the drug, and while by far the most notable example, many other celebrities were well on the bandwagon of the new era of medications.

The rise of these medications was not seen as an unmitigated positive, however. Many critics correctly noted the danger that overuse of psychiatric meds posed. One of the most prominent stand-ups of American comedy, George Carlin, joked that “That’s why we have a drug problem, I really feel, you know, cause everybody has access to drugs … we’re just kinda dopey folks and we have all these drugs available to us … There’s all these drugstores every three or four blocks, you know, big sign: DRUGS.”11 The proliferation and accessibility of addictive psychiatric drugs hit the comic world hard, and their expansion would have a massive effect on the comedic landscape, as many comedians came to deal with substance abuse problems, and then, did what comedians do best: work it into their tight five.

All people are sad clowns. That’s the key to comedy – and it’s a buffer against reality.

Bob Odenkirk, interview with The Guardian 12

SEND IN THE CLOWNS: LET’S TALK STAND-UP

Stand-up comedy as an art form is relatively young. With its roots tracing back to the “stump speech” of minstrel shows in the mid nineteenth century, stand-up as a distinct comedic form came into focus around the 1920s at the tail end of the vaudeville era, where short, comedic monologues served as interstitial acts between the over-the-top sketches typical of vaudeville.13 Early stand-ups like Jack Benny and Bob Hope defined the form, with their rapid fire one-liners and quick distinct bits forming the foundation of stand-up.

The snappy style of older stand-up serves as an interesting frame through which to consider the advent of mental health in comedy. The classic quick quippy style dominant from the 1930s through the 1950s was meant to lampoon a subject on a surface level rather than to deeply examine it. As such, just like with anything else, mental health issues were a punchline, and only the most visible instances of mental illness were highlighted, like suicide, nervous breakdowns, and being plain “crazy.” Serious discussions of mental health were regarded as taboo by many, let alone the glib approach of comedy.

During the 1960s, comedy began to take on a more narrative tone, with stand-ups increasingly eschewing the speedy one-liners of their predecessors, instead opting to tell stories. Such stories ranged from the flippant observational comedy like that of Phyllis Diller, the biting political satire of those like Tom Lehrer, and the irreverent counterculture comedy of stand-ups like Lenny Bruce and the aforementioned Carlin. Shifts toward narrative comedy allowed stand-ups to talk more about their own life in a more candid way, and tackle more complex and difficult topics like race, gender, politics, and of course, mental health. Comedy increasingly became an outlet for malcontents from a variety of backgrounds with different axes to grind, many of whom had an ax to grind with their own mind.14 The rise of narrative styles, coupled with the greater societal visibility that deinstitutionalization created and the use of new psychotropic medications to help mitigate the most severe of mental health challenges, all made for a new freedom for comics to discuss mental health in their routines.

As the twentieth century came and went, the new millennium offered similarly new horizons for comedy. The explosive growth of the internet and subsequent meteoric rise of social media highlighted a critical aspect of comedy that would drive the approach of humor to mental health. Relatabilty became the bread-and-butter of comedy and mental health, audiences responding to honest, candid discussions of issues that so many people face. This era, beginning in the late 2000s and early 2010s is the golden age of mental health in comedy, and while the frequency and way it is discussed has certainly changed, many of the issues at hand are timeless.

This is a situation comedy, no one watches the show to feel feelings. Life is depressing enough already.

Bojack Horseman, “Brand New Couch,” 2015 15

MENTAL HEALTH IN FILM AND TELEVISION

While many of the issues that affected the growth and development of stand-up likewise affected film and television, the way these shifts manifested between the two was markedly different. Despite a handful notable exceptions, portrayals of mental health in media more broadly shied away from the comedic, and tended towards a sensationalized, usually melodramatic frame, and used a remarkably consistent thematic language in their approach.

For over a hundred years, the asylum was synonymous with mental health. Psychiatric institutions’ role as the backdrop for nearly all mental health care for such a long time made it a popular setting for various types of narratives, comic and dramatic. Very often in media, the asylum is portrayed as a severe, cruel landscape, and dramatic portrayal dominate the popular depictions of the asylum, with movies like One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest typifying perceptions of the asylum. Comparatively few comedies take place in the asylum setting, which owes to the general historical trend of the highest profile depictions of mental health being dramas, a trend that has only begun to wane slightly in recent years.

Comedic films about mental health have a smaller imprint on film and television culture. One of the aforementioned notable exceptions above is 1936’s Modern Times, a Charlie Chaplin film that sees his character suffer a nervous breakdown from the stress of his work, and bounce around various institutions to manage him (all while hilarity ensues, of course).16 Of the comedies that do take place in or feature asylums (1950’s Harvey and 1982’s The King of Comedy being good examples), they typically portray a more narrow set of mental health issues, notably delusions and hallucinations, and rarely more “invisible” mental issues like depression and anxiety.

Much like the trends seen in stand-up, depictions of mental health are far more frequent, honest, and in-depth in the modern day. Visual mediums in particular have made frequent and effective use of the “dramady,” “tragicomedy,” or “black comedy,” styles that mix tragic, heavy, or taboo issues with comic elements. Mixed comedic and dramatic styles became quite popular to use to depict mental health, and fit well tonally for many creators.17 Between these two major branches of comedy, a wide array of themes that they have considered come to light, but a few stand out as some of the most enduring.

Humor can be dissected, as a frog can, but the thing dies in the process and the innards are discouraging to any but the purely scientific mind.

E.B. White, in The Saturday Review of Literature, 1941 18

DISSECTING THE FROG OF MENTAL HEALTH IN HUMOR

As a microcosm of the human experience, nearly every disorder, illness, struggle, challenge, etc, has undoubtedly been covered by a comedian. While there are so many avenues, angles, and actual issues to cover, three general areas tend to stick out in depictions of mental health in comedy: substance use and abuse, stress and trauma, and depression, anxiety and suicide. Each comes with its own unique approach, and are worth dissecting a bit. As will become clear, the depictions of these issues became more realistic as mental health became more visible in society, and as less people were institutionalized and more were medicated, mental health issues were more frequently seen, experienced, and interpreted by comics.

Substance Use and Abuse

Perhaps the single most commonly discussed mental health issue in comedy is almost not a mental health issue to begin with. Substance abuse, while not itself a mental health issue, is very often indicative of other underlying problems. The frequency at which substance abuse is discussed in a humorous context warrants a closer look at how substance abuse has been examined in comedy. As Carlin noted earlier, many of the problems with substance abuse stem from the expansion of psychiatric meds that came along with deinstitutionalization. Those medications were easily given to people who needed it, but many of those same people developed an addiction to those substances, overmedicating or self-medicating to cope with their mental illness.

Others used entirely illicit substances–some began with legal medications, and moved to illegal drugs when legal ones became unavailable or ineffective. Richard Pryor recounts his experience with crack cocaine and how he had used it to cope, and describes his experience hiding his crack problem from a friend, and the allure of the pipe that he uses and how it “talks” to him.

Outside of the world of stand-up, television has also tackled substance abuse to varying degrees of humor and authenticity, often opting for a hybrid “dramady” approach as mentioned earlier. These examples tend modern, as good comedic portrayals of substance abuse become more sparse further back. The medical drama House M.D. features a diagnostic savant in the titular Dr. House, who has a severe Vicodin addiction. While the show is predominantly a drama, its comedic elements frequently revolve around the sardonic wit of House, and the hijinks that his substance abuse often gets him into.21

Trauma and Stress

Post traumatic stress is a curiously common depiction in comedy. The 1980 movie Airplane! sees its main character suffer flashbacks to “the war” and suffers a “drinking problem” as a result. At the time near its release, post traumatic stress was still stigmatized, and thought to only affect soldiers and others caught in war. This levity surrounding such trauma may well represent a disregarding of stress disorders as serious issues, but made possible by the greater visibility of the afflicted due to a lack of supporting psychiatric institutions.

George Carlin similarly speaks on the issue of post traumatic stress, and laments the euphemism creep of traumatic stress, reasoning that the “softening of language” that developed with stress disorders prevented adequate help for its sufferers.

Generational trauma, and the effect that it has on mental health has become an increasingly common topic in comedy in recent times. Bojack Horseman, an animated sitcom that has garnered critical acclaim for its depictions of mental health, follows the titular Bojack, an anthropomorphic horse who is a washed up sitcom star from the 90s, and deals with his personal relationships as he abuses substances in a self destructive pattern in an effort to self medicate severe depressive tendencies. Both Bojack himself and his close friend Diane in particular struggle with generational trauma, with Bojack suffering through an abusive childhood at the hands of his parents and turning to drugs and alcohol to cope, and Diane being relentlessly bullied by her family turns to writing as a way to make “something good” out of her trauma.

Depression and Suicide

Perhaps the most common way that comedy talks about mental health is about suicide, and as an extension, major depression. Jokes about depression and suicide are some of the oldest ways mental health was confronted, as suicide in particular was a very visible issue of mental health and regarded with little complexity, making it comparatively easy to quip about.

Like Hope, comedians like Bob Newhart confronted issues of suicide with a bit more tact, but were still rather glib with their depictions. In his 1960 “Ledge Psychology” routine, he employs his classic one-man dialogue style to recount a fictional encounter with a suicidal man on the edge of the building, with him variably encouraging the man to return from the ledge, or to go on and jump off.

Modern depictions of depression are far more in depth than the quips of the past, and focus on the everyday struggles of living with depression, a feat made possible in part by medications like Prozac and other antidepressants that many struggling comics may take.

Laughter gives us distance. It allows us to step back from an event, deal with it and then move on.

Bob Newhart

CONCLUSION

All things considered, this is a narrow look at the constellation of depictions of mental health in comedy, and of course media in general. Not only is mental health depicted in comedy far more frequently than ever before, but it is also done more widely than ever before; increasingly popular comedic mediums like internet memes warrant an entire conversation of its own. Counting passing references, starting from the early days of stand up comedy and considering the menagerie of mental health issues included in the DSM-V, trying to cover that all here would be a fools errand.

It is because of the seismic shift in mental health care that deinstitutionalization and psychiatric medication created that there are nearly this many examples to choose from. Without their influence, it is not impossible to imagine a world most comics still only tell their one liners, and audiences are never treated to candid explorations of deeper struggles, not unlike other taboo subjects in comedy are treated nowadays.

Comedy is a fluid art form, one that is very sensitive to the temperature of society at large. Just as much as it is a product of societal attitudes, so too can it move the needle of acceptance and understanding. It is also a process of coping, and healing, and dealing with some of the most intractable issues one can face. Comedy is one of humanity’s most powerful tools for these things and more, and understanding its relationship with our mind and how that relationship has grown and changed is one of the best ways to keep on laughing and smiling our way through the day.

That’s all, folks.

NOTES

- Kimberly Senior, dir., Chris Gethard: Career Suicide. HBO, 2017.

︎

︎ - Anthony McCartney, “Coroner: Sleep Apnea Among Causes Of Carrie Fisher’s Death,” The Associated Press, June 16, 2017. https://tinyurl.com/yh9rpvn2

︎

︎ - Daniel Kreps, “Carrie Fisher’s Ashes Placed in Giant Prozac Pill Urn,” Rolling Stone, January 7, 2017, https://tinyurl.com/4zdn9bzr

︎

︎ - Carrie Fisher, Wishful Drinking (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2008).

︎

︎ - Ibid.

︎

︎ - Gerald N. Grob, Mad Among Us: A History of the Care of America’s Mentally Ill (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1994).

︎

︎ - Nellie Bly, Ten Days in a Mad House; Or, Nellie Bly’s Experience on Blackwell’s Island (New York: Norman L. Munroe, 1877).

︎

︎ - George W. Paulson, Closing the Asylums: Causes and Consequences of the Deinstitutionalization Movement (Jefferson, N.C: McFarland & Co., 2012).

︎

︎ - Spike Lee, dir., Katt Williams: Priceless: Afterlife, HBO, 2014.

︎

︎ - Andrea Tone, The Age of Anxiety: A History of America’s Turbulent Affair with Tranquilizers (New York: Basic Books, 2008).

︎

︎ - George Carlin, “Drugs, ” Side one, track four on FM & AM, 1972. Youtube.

︎

︎ - Bob Odenkirk. “Bob Odenkirk: ‘All People Are Sad Clowns. That’s The Key To Comedy,’” interview by Rebecca Nicholson, The Guardian, April 15, 2017. https://tinyurl.com/42tzryz8

︎

︎ - Wayne Federman, The History of Stand-Up: From Mark Twain to Dave Chappelle. (Independently Published, 2021).

︎

︎ - Rebecca Kreifting, All Joking Aside: American Humor and its Discontents (Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 2014).

︎

︎ - Bojack Horseman, season 2, episode 1, “Brand New Couch,” directed by Amy Winfrey, written by Raphael Bob-Waksberg, aired July 17, 2015, https://www.netflix.com/80048076, 00:16:48.

︎

︎ - Chaplin, Charlie, dir. Modern Times. 1936; Los Angeles, United Artists.

︎

︎ - Olga Khazan, “The Dark Psychology of Being a Good Comedian.” The Atlantic, February 27, 2014. https://tinyurl.com/5b33kyju.

︎

︎ - E. B. White and Katharine S. White. “The Preaching Humorist” in The Saturday Review of Literature (October 18, 1941): 16.

︎

︎ - Alex Timbers, dir., John Mulaney: Baby J, Netflix, 2023. https://www.netflix.com/title/81619082.

︎

︎ - Joe Layton, dir., Richard Pryor: Live on the Sunset Strip, Self produced, 1982.

︎

︎ - David Shore, House, M.D., Universal Televison, 2004.

︎

︎ - David Zucker and Jerry Zucker, dir. Airplane!. 1980; Los Angeles, CA: Paramount Pictures.

︎

︎ - Rocco Urbisci, George Carlin: Doin’ It Again, HBO, 1990.

︎

︎ - Bojack Horseman, season 6, episode 10, “Good Damage,” directed by James Bowman, written by Raphael Bob-Waksberg and Joanna Calo, aired January 30, 2020, https://www.netflix.com/81026968, 00:16:30.

︎

︎

Bibliography

Berger, Phil. The Last Laugh: The World of Stand-up Comics. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2000.

Burton, Juliette. “No Fooling Around: Humour and Mental Health.” MQ Mental Health Research, March 31, 2023. https://www.mqmentalhealth.org/no-fooling-around-humour-and-mental-health/.

Eagleton, Terry. Humour. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2019.

Eil, Philip. “Depression Is No Joke. So Why Are Comedians so Good at Talking about It?” Boston Globe, September 3, 2021. https://tinyurl.com/47ruhfsm

Federman, Wayne. The History of Stand-Up: From Mark Twain to Dave Chappelle. Independently Published, 2021.

Gelkopf, Marc. “The Use of Humor in Serious Mental Illness: A Review.” Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine (January 1, 2011): 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1093/ecam/nep106.

Gibson, Janet M. An Introduction to the Psychology of Humor. London: Routledge, 2019.

Grob, Gerald N. Mad Among Us: A History of the Care of America’s Mentally Ill. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1994

Healy, David. Let Them Eat Prozac: The Unhealthy Relationship between the Pharmaceutical Industry and Depression. New York: New York University Press, 2004.

Khazan, Olga. “The Dark Psychology of Being a Good Comedian.” The Atlantic, February 27, 2014. https://tinyurl.com/5b33kyju

Kramer, Peter D. Ordinarily Well: The Case for Antidepressants. First edition. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2016.

Kreifting, Rebecca. All Joking Aside: American Humor and its Discontents. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 2014.

Lamb, H. Richard, and Linda E. Weinberger. Deinstitutionalization: Promise and Problems. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2001.

McCartney, Anthony. “Coroner: Sleep Apnea Among Causes Of Carrie Fisher’s Death.” The Associated Press, June 16, 2017. https://tinyurl.com/yh9rpvn2

Mizejewski, Linda. Hysterical!: Women in American Comedy. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2017. https://doi.org/10.7560/314517.

Paulson, George W. Closing the Asylums: Causes and Consequences of the Deinstitutionalization Movement. Jefferson, N.C: McFarland & Co., 2012.

Pereira, Ann, and Sarika Tyagi. “Mental Health and Stand-up Comedy: ‘Unhappy’ Stand-up Comedy as a Reflection of Liquid Modernity.” Studies in Media and Communication 10, no. 2 (2022): 279-87. https://doi.org/10.11114/smc.v10i2.5785

Phelan, Jo C., Bruce G. Link, Ann Stueve, and Bernice A. Pescosolido. “Public Conceptions of Mental Illness in 1950 and 1996: What Is Mental Illness and Is It to Be Feared?” Journal of Health and Social Behavior 41, no. 2 (2000): 188–207. https://doi.org/10.2307/2676305.

Sawallisch, Nele. “‘Horsin’ Around’? #MeToo, The Sadcom, and BoJack Horseman.” Humanities 10, no. 4 (October 29, 2021): 115. https://doi.org/10.3390/h10040115.

Tone, Andrea. The Age of Anxiety: A History of America’s Turbulent Affair with Tranquilizers. New York: Basic Books, 2008.

“The Top 300 Drugs of 2020.” CliniCalc. Accessed November 14, 2023. https://clincalc.com/DrugStats/Top300Drugs.aspx

Primary Sources

Bob-Waksberg, Raphael. BoJack Horseman. Tornante Television, 2014. https://www.netflix.com/title/70300800.

Bloom, Rachel. I Want To Be Where The Normal People Are. London: Coronet, 2020.

Burnham, Bo, dir. Inside. Netflix, 2021.

Chaplin, Charlie, dir. Modern Times. United Artists, 1936.

Fisher, Carrie. Wishful Drinking. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2008.

Koster, Henry, dir. Harvey. Universal Pictures, 1950.

Mercado, Kristen, dir. Taylor Tomlinson: Look at You. Netflix, 2023. https://www.netflix.com/title/81471774.

Odenkirk, Bob. “Bob Odenkirk: ‘All People Are Sad Clowns. That’s The Key To Comedy.’” Interview by Rebecca Nicholson. The Guardian, April 15, 2017. https://tinyurl.com/42tzryz8

Pryor, Richard. Pryor Convictions: And Other Life Sentences. Los Angeles: Barnacle Books, 2018.

Scorsese, Martin, dir. The King of Comedy. Embassy International Pictures, 1982.

Senior, Kimberly, dir. Chris Gethard: Career Suicide. HBO, 2017.

Sloss, Daniel, dir. Daniel Sloss: X. HBO, 2019.

Timbers, Alex, dir. John Mulaney: Baby J. Netflix, 2023. https://www.netflix.com/title/81619082.

Urbisci, Rocco, George Carlin: Doin’ It Again. HBO, 1990.

Weir, Peter, dir. The Truman Show. Paramount Pictures, 1993.

Zucker, David, and Jerry Zucker, dir. Airplane!. 1980; Los Angeles, CA: Paramount Pictures.

Week 14 Digital Resource Blog Post

This clip is from an episode of House about a woman with schizophrenia. The scene here, like much of the episode, focuses on her son and the struggles that he had caring for his mother with the limited support available. This reminded me, although the situations are reversed, of Pete Earley’s struggles in caring for his son through his mental illness.

Week 14 Blog Post

This article on involuntary mental health treatment(s) was very informative. The article discusses the various methods of classifying whether or not someone should be receiving involuntary mental health treatment, as well as the criteria/attributes they would have to show to be deemed eligible. In particular, Anuja Kumaria’s (Senior Attorney at the Law Foundation of Silicon Valley) quote stuck with me: “We understand that family is important; they are the support systems often,” “However, ultimately, when it comes to involuntary treatment, it’s the individual whose civil liberties will be jeopardized.” Kumaria acknowledges the importance of the family in the process of rehabilitation. Still, she maintains that there is a certain point where there should be outside intervention, which is where involuntary treatment comes into play. The article emphasizes that while the line of when it’s deemed appropriate to implement involuntary treatment methods has long been stained gray, there are methods and means of measuring the level of danger one poses to themself, and to others, and this is a main part of how psychiatrists determine if someone is in need of involuntary treatment. #histmental2023

Interview with Pete Earley

“Drug Addiction in American Housewives”

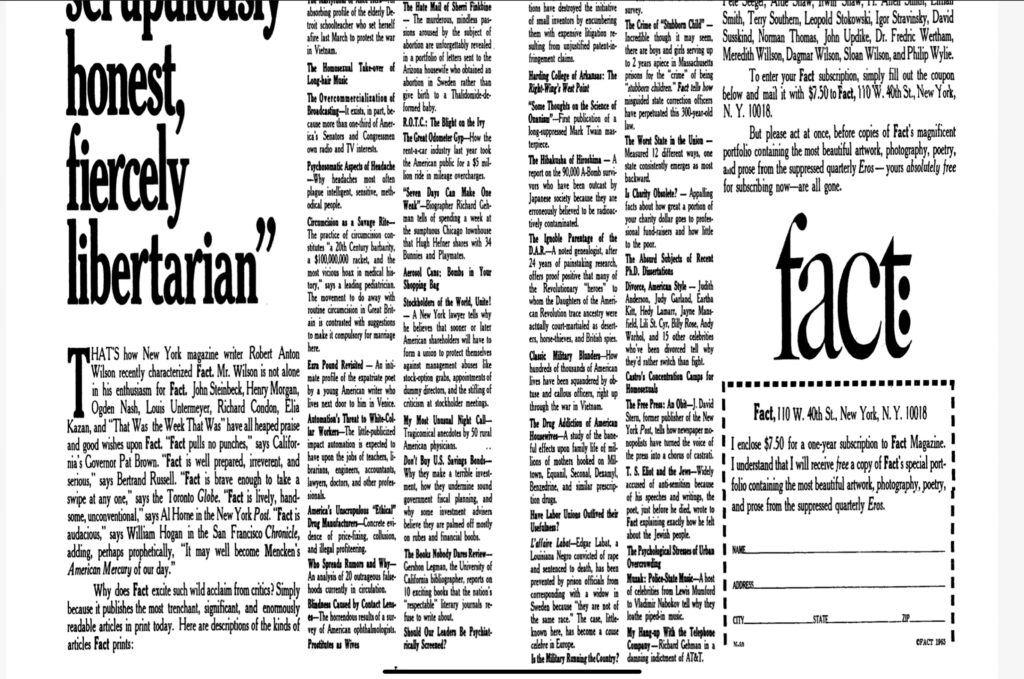

This display Ad from the New York Times in the 1960s advertising “Fact” shows an interest in studying drugs that are correlated for use with American Housewives.

Week 12 Digital Resource Post

This instagram reel was made by a woman who makes a lot of “day in the life” content about being a stay at home mom home schooling her two young sons. In her posts, she is often dressed very beautifully and her home and life overall seem very happy and serene. Naturally, the comments on her posts are often filled with people alleging that she must be on some type of psychiatric medication in order to maintain this “perfect” life maintaining her home and caring for her kids. She at times plays into this, as was the case in this video where she recounts some things she does to practice self care, which includes a “post lobotomy appointment.” Both her post as well as the reaction to her regular content reference the association between white, middle class housewives and psychiatric care such as medications and lobotomies, with the implication that the traditional expected role for women is not something that can be achieved happily without some sort of intervention.

Movie Review: Silver Linings Playbook (2012)

The film I chose to look at is Silver Linings Playbook (2012). The movie follows the main character, Patrick’s, release from his court ordered stay at a mental institution. The story focuses on Patrick’s adjustment to being back at home and trying to “fix everything” while navigating his illness.

Patrick is diagnosed with bipolar disorder. The film depicts his disorder with three major attributes: extreme mood swings, paranoia, and aggression. All of which are stereotypical traits of bipolar disorder. Pat’s mood swings are extreme and happen when he is triggered by his own overactive brain. He will have a perfectly fine day, but once left with his own thoughts (usually thoughts about his past relationship which is a causation for his institutionalization) for fifteen minutes, becomes argumentative and violent. His paranoia and delusions are spelled out the entirety of the film, as he is constantly paranoid about people “being out to get him” and constantly delusional about his current self compared to his past self. All of his actions throughout the entire film are devoted to him becoming better in order to go back to his way of life prior to his institutionalization. However, his delusions play the role of convincing him he’s in a better spot by feeding himself news of his ex-wife wanting him, or being automatically cured through his performative actions. All of these attributes are well-known symptoms of bipolar disorder, and the film does a good job of not making his illness into a joke to conquer like most do. However due to the nature of the film being set around one particular person’s experiences, it obviously does not encapsulate the disorder in its entirety and mainly relies on the more stereotyped bits and pieces to convey.

Along with the depiction of bipolar disorder, this film illustrates the stigma of mental disorders and how they affect day to day perceptions of those who are diagnosed. Pat’s parents, while extremely supportive of him, are embarrassed about his mental state at the beginning of the film and convince themselves that there is nothing wrong with their son. Consequently feeding into Pat’s own delusions about his mental wellbeing. Further, Pat’s brother and his friends perceive Pat’s illness as a joke and call him various names, such as “crazy” and “loon”, overall making a joke out of his disorder and the fact he was institutionalized. This embarrassment comes from the fact that throughout history mental illness has been treated as something taboo, and if you are affected by it, you should be ashamed of. The film did an excellent job of representing how the perception of mental illnesses affect how the public treats those affected.

Overall, while a little one dimensional, it is obvious the writers of this movie did put in effort to portray mental disorders well by humanizing those who live with them and not making them out to be monsters.

Movie Discussion

The movie I chose to discuss is Shutter Island. This movie was directed by Martin Scorsese and was released in 2010. This movie stars Leonardo DiCaprio as “Teddy Daniels”, a US marshal and former World War Two veteran. Teddy is sent to Shutter Island to find a patient that has gone missing. The story takes place in 1954 and was pretty historically accurate as far as the care and conditions of the mental asylum.

Something that stood out was when Teddy asked Dr. John Cawley about the type of treatment conducted on Shutter Island. John Cawley replies that there are two schools of thought in psychiatry: the “old school” and the new school”. The doctor then goes on to explain how the old school is focused more on caretaking explaining the use of unethical surgeries like lobotomies. This was true of American asylums in the decades prior to the 1950s. As the lobotomy had been used during the 1930s. The doctor also tells Teddy that the new school focused on humane treatment, medicine, and curing. Which translates as the 1950s saw an increase in the search for medicinally based treatment. Most significant was the creation of Thorazine or Chlorpromazine, the first antipsychotic. Which is mentioned countless times throughout the movie and was seen as the best drug at the time.

The asylum itself is accurate. First is that the asylum was placed on an island away from the city. This was common for asylums as they had developed an “out of sight out of mind” idea. Another scene shows patients sleeping quarters which were just a giant room filled with beds. This is subtle yet shows the issues of overcrowding that overtook asylums in the early 1900s. At the beginning of the movie Teddy sees a lobotomized patient. The appearances are over exaggerated however, it shows the effects that asylums had on the physical body. Another example of this is when we meet George Noyce who is extremely skinny and beat up.

The effect of past trauma is something that is touched upon. It is mentioned to Teddy when he discusses his past. Linking current behaviors to those experiences which is something the Freud’s Psychoanalysis touched upon. The focus is mostly PTSD is discussed in Shutter Island. Teddy having liberated Dachau is plagued by nightmares and flashes of the horrors that he had seen there. The doctor’s reactions to it made sense during the time. John Cawley referred to one of these flashes as a migraine and urged Teddy to take an aspirin. This lines up with knowledge at the time as after World War Two as the term PTSD did not exist and there was little understanding of it.

While the story is fictional, many of the small details are not. Whether it be the philosophy of American psychologists or the physical building this movie fits what we have learned. As it stands the movie offers real information in an extremely entertaining way. 8.5/10.

Citations

Psycho War Clip

“Dr Cawley Psychotherapy War – Shutter Island (2010) – Movie Clip HD Scene.” YouTube, May 9, 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=du5V3hyGXNA.

Who are you clip

Image

Sarapampuriportfolio. “Movie ‘Shutter Island’ (2010) – Review – Blog of Sara Pampuri.” Sara Pampuri, January 24, 2021. https://sarapampuriportfolio.altervista.org/en/movie-shutter-island-review/.