During the twentieth century America had been overcome by the fight for civil rights. After many years of fighting, the 19th amendment was passed in 1920 giving women the right to vote. This was shortly followed by the passing of the Indian Citizenship Act in 1924. After that was the civil rights movement of the 1950s-1960s. Amongst all the fighting for civil liberties there was another group of individuals who fought for their rights and won. That being the patients in mental asylums. In some cases, patients had been placed in these asylums for little or no reason at all forcing them to take an involuntary “life sentence” at one of these asylums. During the second half of the twentieth century life for the “mentally ill” changed throughout America. After gaining their freedom they were thrown into a world that had all but forgotten about them. This paper will argue that while the second half of the twentieth century was “revolutionary” for Americans dealing with mental disabilities, these changes would only work to further ostracize those individuals from the rest of society.

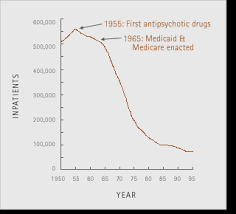

In 1950 there were over 500,000 patients in insane asylums across the United States. The extremely high number of patients in asylums was something that the joint commission had aimed to change, in the “Action for mental health: Final report of the Joint Commission on Mental Illness and Health” it is noted as saying “The objective of Modern treatment of persons with major mental illness is to enable the patient to maintain himself in the community in a normal manner.” (Action for Mental Health).” This was published in 1961 and would spark the “revolution” that took place. The idea of these patients getting back into the community was executed in a top-down manner. The first step federally was the Community Mental Health Act signed in 1963.

This act shifted federal funding from hospitals to community mental health programs and centers. The signing of this act meant that responsibility for the mentally ill was slowly being pushed back upon society. This was in stark contrast to the idea of care taking that had been developed amongst American mental asylums. While the 1963 act and others during the 1960s-1970s were seen as wins for civil rights, these individuals were put into an unforgiving society. Now one of the major issues facing society was the number of individuals that were released in such a short time span. In “‘Community Care’: Historical Perspective on Deinstitutionalization” author Andrew Scull states that “the dramatic decrease took place between 1965 and 1980, when numbers fell from 475,202 to 132,164.” (71, Community care).

On the surface it appears as though treatment had taken a substantial leap. However, that was not the case rather individuals were being thrown out of asylums and into the community. When these former patients were reintroduced, they were met with a society that treated them as outcasts and figuratively continued the mistreatment that they had faced in the asylums. With over 300,000 of the “mentally ill” being released into society it appeared to overwhelm America. During the time it is noted that “Their plight triggered popular fears of dangerous “maniacs” running the streets and invading neighborhoods” (folklore). This clearly shows that these individuals would not be immediately “adapted” into society the way that they were intended to. As a result of this many former patients found themselves with no one to turn to in a society which was content ignoring them. Leaving them to seek shelter in welfare hotels, halfway houses, and homeless shelters. For these patients they went from a place of stability, directly to the “lowest rank” of American society.

Another thing that fueled negative feelings towards former patients’ is that their actions “went against societal norms.” While there is a discussion to be had about what norms are, who sets them, and how one should conduct themselves to fit these norms. We should turn the focus on how going against these norms impacted societies view of the mentally ill. Similar, to the days before asylums community care took over as the chief way to care for those with mental disabilities. During the twentieth century America had become a progressive nation so, it was reasonable to believe that these individuals could seamlessly integrate into society. The major issue was that society had retained the same negative stigmas about mental illness that led to the overcrowding and hiding away of these individuals. These beliefs are perfectly exemplified in the “Action for Mental Health Report” written by the Joint commission in 1961. It states that “They do not feel as sorry as they do relief to have out of the way persons whose behavior disturbs or offends” (Action for mental Health, 58). The significance of this quote is that it shows the overall lack of empathy towards mentally ill Americans during this time. It speaks to the fact that most Americans would rather these individuals be locked away than “deal with” their behaviors. For many these asylums had become places to “drop off’ unwanted or troublesome individuals. In a turn of events the states were the ones dumping off patients. America answered with a lack of empathy for these individuals, which is a problem considering that is a major part of community care.

Aside from convenience there was another driving factor in the ostracization of the mentally ill in America. Since they had been “hidden away” for so long, many Americans didn’t know what to make of these “newly” added individuals. So, from societies perspective the “strangeness” of their actions helped to further solidify their ideas of the mentally ill. Along with strange behaviors there was a general lack of understanding of what mental illness is especially in the broad society’s knowledge. With a lack of empathy, a more damaging societal view emerged. It is noted that “It has been observed countless times that sight or thought of major mental illness, as our culture has come to understand it, stimulates fear” (Action for mental Health Report, 59). This sort of fear of the unknown that Americans had developed created a new set of problems more significant than “fitting in” to society. Not only did patients have to face the transition into society they had to do it in a world that actively feared them for factors that were out of their control. It is important to note that this quote is from 1961 but this sentiment carried throughout the rest of the century.

More concrete proof of Americans fear of the mentally ill can be seen in the way that popular media took off with its portrayal of mental illness and mental health facilities. The most prevalent of which can be seen in popular American movies during the back half of the twentieth century. In “The Folklore of Deinstitutionalization: Popular Film and the Death of the Asylum, 1973–1979” author Troy Rondinone discusses the connection between horror movies produced during this time and “fears” Americans had. Rondinone specifically mentioned “The Exorcist”, “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s nest”, and “Halloween.” These films were met with immense popularity and are still considered classics to this day. However, Rondinone notes that “The movies folklorically confirmed popular horrors of mental hospitals, and the people trapped inside them.” (folklore). The negative portrayal of mental health and mental institutions in these movies further differentiated the former patients from the rest of society.

The ostracizing of former patients is not only seen in popular media, but it can also be seen in the “transferring” of these patients. After these individuals had gained their freedom, they were essentially just sent off to other institutions. In the 1960s and into the early 1970s most of the patients being moved out of asylums were individuals over the age of 65. Many Americans saw these individuals as burdens and lacked either the means or want to care for them. This can be seen when Andrew Scull states that “Between 1963 and 1969 alone, the numbers of elderly patients with mental disorders living in nursing homes increased by nearly 200,000, from 187,675 to 367,586. By 1972, … the mentally disturbed population housed in nursing and board and care homes had risen to 640,000.” (75, community care). With the run of the American asylum ending families looked for a new place to “dump off” these unwanted individuals. Reinforcing the the idea of hiding away these individuals had persisted through societal changes.

For younger patients they were not lucky enough to be put back into “care” facilities. Previously, “odd” behaviors got people sent to an asylum now they were sent to jail instead. The Book “From Asylum to Prison: Deinstitutionalization and the Rise of Mass Incarceration after 1945” looks at Philadelphia and the polices reaction to the recently released patients. The book notes that Philadelphia police commissioner “published a directive that encouraged police to take people exhibiting antisocial behavior to jail, since they could no longer take them to hospitals involuntarily.” (Community Care, 98). This was seemingly a quick fix to the problem of unwanted people. It is important to note that this attempt to hide away these members of society was not exclusively a Philadelphia thing. It is also noted that “the number of people diagnosed with mental illnesses entering the prison system sharply increased, a trend that occurred in countless cities across the United States” (Community Care, 98-100). This sort of “institutional transfer” that occurred showed how American society had wished to rid themselves of these individuals as soon as they got their rights. Americans’ willingness to hide these individuals speaks the truth that many of the former patients never had a real chance of making it in American society.

While the twentieth century was one where many people gained their rights that does not mean that all citizens were in favor of it these changes. In the case of the mentally ill deinstitutionalization was met with negativity from the majority of American citizens. As far as public perception many Americans feared these individuals. This fear would be further exemplified by movies that painted mental illness as scary, increasing the spread of this fear. As a result of this fear Americans worked to “re-institutionalize” former patients. Whether that be dropping a grandparent off at a nursing home or sending individuals to jail instead of asylums, America worked to hide away these people. Overall, the deinstitutionalization of the mentally ill was met by an America that wanted to push them out of society.

Citations

Parsons, Anne E. From Asylum to Prison: Deinstitutionalization and the Rise of Mass Incarceration after 1945. The University of North Carolina Press, 2018.

RONDINONE, TROY. “The Folklore of Deinstitutionalization: Popular Film and the Death of the Asylum, 1973–1979.” Journal of American Studies 54, no. 5 (2020): 900–925. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021875819000094.

Scull, Andrew. “‘Community Care’: Historical Perspective on Deinstitutionalization.” Perspectives in Biology and Medicine 64, no. 1 (2021): 70–81. https://doi.org/10.1353/pbm.2021.0006.

Bennett, Douglas. “Deinstitutionalization in Two Cultures.” The Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly. Health and Society 57, no. 4 (1979): 516–32. https://doi.org/10.2307/3349726.

Action for mental health: Final report of the Joint Commission on Mental Illness and health, 1961. New York: John Wiley and Sons, 1961.

Images

“Kennedy’s Vision for Mental Health Never Realized.” USA Today, October 20, 2013. https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2013/10/20/kennedys-vision-mental-health/3100001/.

Raphael, Steven, and Michael A. Stoll. “Assessing the Contribution of the Deinstitutionalization of the Mentally Ill to Growth in the U.S. Incarceration Rate.” The Journal of Legal Studies 42, no. 1 (2013): 187–222. https://doi.org/10.1086/667773.

“Social Norm Examples.” YourDictionary. Accessed November 9, 2023. https://www.yourdictionary.com/articles/examples-social-norms.

“Deinstitutionalization – Special Reports | The New Asylums | Frontline.” PBS. Accessed November 9, 2023. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/asylums/special/excerpt.html.

Video

YouTube. YouTube, 2008. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2WSyJgydTsA.